Written by Communications Associate, Jarea Fang

Climate change is a scary reality whether you’re on the leading edge of climate research or an individual experiencing the impacts of it. In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared climate change to be the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century. According to a 2021 multinational survey study, most physicians and medical students believe they know little about climate change, despite many American adults considering their primary care physicians a trustworthy source for health information regarding global warming.

As our world continues to feel the extreme effects of climate change, demand for health professionals will only go up. In 2016, however, a study revealed that many American healthcare systems have devastating impacts on the environment. If the US healthcare system was a country, it would be the world’s 13th-largest emitter of greenhouse gases! This is more than the emissions of the entirety of the UK, and more than any other healthcare system on the planet.

This brings up an ethical dilemma, as all doctors pledge to “do no harm” as part of the Hippocratic Oath: Is there a way to serve individual patients without impacting the rest of the human and ecological population through downstream healthcare pollutants and emissions? Or is there at least a way to mitigate the current impact?

Joshua Perez-Cruet, a second-year medical student at WashU’s School of Medicine (WUSM), is working on addressing this dilemma. By drawing on his own research as well as input from his classmates and expertise from medical faculty, he has been putting together an ambitious curriculum that directly addresses the intersection between climate change and medicine. By training a new generation of sustainability-oriented doctors, Josh hopes to do his part in shifting US healthcare toward a greener, healthier future.

How it Started

The story of WUSM’s new climate-focused medical curriculum begins at Josh’s lunch table, where he has hosted informal discussions on climate change and health topics for the WUSM Environmental Sustainability Group.

“It was all fairly simple stuff,” Josh claims, “like how heat affects different chronic illnesses, or how climate change impacts the spread of vector-borne diseases, parasites, and waterborne diseases.”

While the lunch talks were well-attended, Josh worried for the rest of his classmates. The more students he spoke to, the more he began to suspect that discussions of climate change in the medical school curriculum were lacking. So, he did some digging. This resulted in the stunning discovery that only one relevant paragraph of an assigned reading and three lecture slides even mentioned climate change in the entire year and a half of WUSM’s preclinical curriculum.

Ever since then, preliminary ideas of a climate-focused medical curriculum began trickling into his mind.

“I felt really small, being at a new institution and not knowing too many people,” he shares, recalling the anxieties of being a first-year medical student with a big dream. “Fortunately for me, nearly everyone I’ve reached out to for help has been overwhelmingly supportive and enthusiastic to share their expertise—such as WUSM sustainability coordinator, Heather Craig; Dean for Education, Dr. Eva Aagaard; WUSM Health Equity and Justice Lead, Audrey Coolman; and Director of WUSM’s Medical Education Research Unit, Dr. Janice Hanson to name a few.”

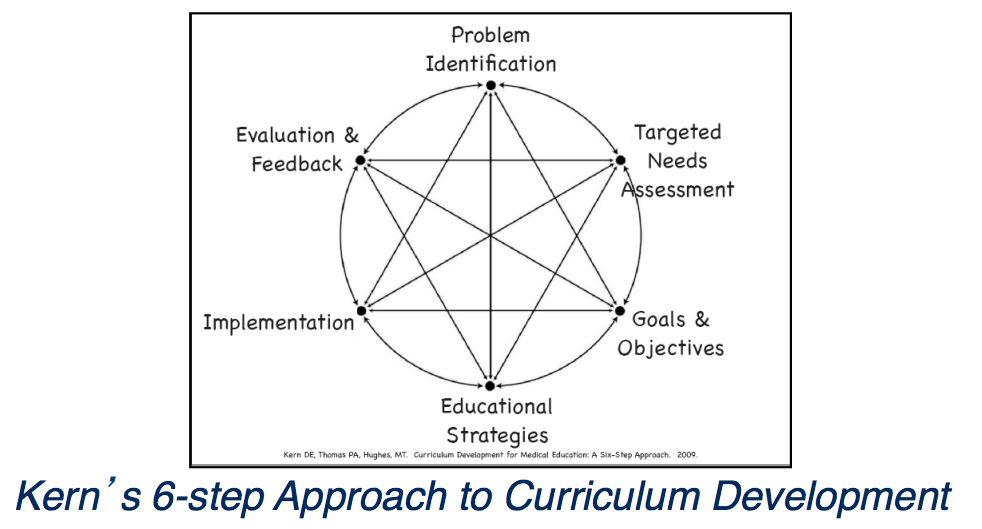

To design this curriculum, Josh is following the six-step process of medical education curricular design. He first identified the need for a climate curriculum, and then researched previously published models. During WUSM’s Explore Immersion, he chose the Education Pathway. This opportunity provided him with a month of training in medical education, strong personalized mentorship, and effective collaboration with other students on this scholarly project. With help from students and faculty, he set goals and learning objectives, and then developed educational strategies. Before long, he implemented a pilot curriculum and is currently evaluating assessments and feedback, joined by more and more passionate students, staff, and faculty.

“Suddenly, we had fifteen to twenty people working on the curriculum—if you count the faculty and staff giving the feedback,” Josh explains, grateful for the help. “Having the project informed by diverse views and strengths is generating a far more robust curriculum than the one I envisioned.” He is still working to expand his team.

How it’s Going

One foundation of Josh’s climate-focused medical curriculum is for students to understand the primary cause of climate change, which is human-generated fossil fuel emissions. Students should also know that the rise in global temperature and extreme weather patterns disproportionately harm minoritized and vulnerable populations of the world.

In the latest Sustainable Action Team (SAT) Meeting, Josh gave a presentation about his work and showed some maps from the 2018 St. Louis Climate Vulnerability Assessment. He explained that the rise in global temperature from fossil fuel consumption impacts heat-related emergency room visits. Moreover, the urban heat island effect causes temperatures in urbanized areas to rise higher than surrounding greener regions—4 oF higher, for example, in St. Louis where heat-related emergency room visits are disproportionately higher for those living in the predominantly Black North St. Louis. Climate change also impacts the quality of the air we breathe, as particulate matter from combustion of fossil fuels led to approximately 1 million deaths in 2019. Similar to the data for heat-related emergency room visits, African American children had 8.5 times more emergency room visits for asthma at St. Louis Children’s Hospital than their white peers in 2015.

Another important foundation for this climate-focused medical curriculum is empowerment. “A lot of times when I hear about climate change, it’s talked about in a way that really quenches hope,” Josh explains. “So I wanted to identify areas of the hospital that have profound environmental impacts, and then offer strategies for how to mitigate or reduce those impacts.” He has also prioritized featuring how hospitals have successfully implemented these strategies.

Supply chain emissions, unsurprisingly, are by far the greatest contributors of healthcare’s total greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for approximately 60-70% of the US healthcare system’s carbon footprint. A few hospitals are spearheading initiatives to strongly reduce supply chain emissions, and the Kaiser Permanente Health System has taken great strides to directly tackle this issue after successfully eliminating on-site emissions.

A lesser known fact is that anesthetic gases account for 5% of the hospital’s on-site greenhouse gas emissions. This is because most anesthetic gases are potent greenhouse gases: one hour of desflurane (a general anesthetic gas) generates similar emissions to driving 230 miles in a conventional car. Thus, Barnes Jewish Hospital has been phasing out desflurane and replacing it with sevoflurane, another anesthetic gas. One hour of sevoflurane use has the emissions of driving 30 miles by car. By simply informing healthcare staff of more sustainable alternatives and practices like responsible anesthetic gas use, the hospital system can significantly reduce the negative environmental consequences associated with serving individual patients.

Coming Up Next

MedEdPORTAL, one of the most trusted resources on health professional training, recently put out a call for submissions to “Climate Change and Health Curricula,” which Josh views as “an extraordinarily inspiring concurrence.” To publish materials to this source is a great honor in the world of medicine, so Josh hopes to do so one day after further development and curricular evaluation.

“I’m currently working with a team of students and professors to integrate slides on the impact of climate change on specific diseases into pre-existing lectures, and am in very early stages of discussing integration into the curricula of other health professions schools here,” Josh explains. “We still have lots of work to do.” He anticipates that in a few years, he will find more and more like-minded individuals at other institutions designing and publishing similarly important modules.

To contact Joshua Perez-Cruet, please email him at j.m.perez-cruet@wustl.edu. He would love to speak to you about anything in this newsletter article; about his all-time favorite invertebrate, the Drunella, a mayfly genus serving as a great indicator of river health; or about Colorado’s Greenback Cutthroat Trout, which has “a most inspiring story of ecological resilience to human perturbation.”

Josh’s List of Resources

- The Lancet Countdown Report is a collaboration of 43 different academic institutions and is updated every year. It’s an excellent source for those interested in a deeper dive into climate change and health, the best evidence for impacts of climate change on health, and future actions that must be taken.

- The St. Louis Climate Vulnerability Assessment of 2018 was developed to better understand the potential consequences of increasingly extreme weather events brought on by climate change, the conditions most likely to affect the residents of the City of St. Louis, and those who are most vulnerable to these events.

- The Global Consortium on Climate Change and Health has an abundance of resources on climate change and health. Josh particularly recommends the Climate and Health Responder Course for Health Professionals. He used this resource for his lunch talks on the impact of climate change on diseases.

- Practice Greenhealth offers tons of case studies of how hospitals have successfully implemented sustainability initiatives.

- Josh shared his work through the presentation “Integrating Climate Change into Medical Curriculum” at the Sustainability Action Team (SAT) Meeting on September 21st, 2022.